Our power over their pleasure

We like to think we offer solidarity and empowerment to activists in the global South. It can shift into intrusion and co-dependency. A story about vibrators, among others.

I have been wanting to write this for a long time.

It leads up to a story about vibrators. That’s not titillating click-bait. This story really happened last summer. It struck me, and stuck with me, as a profound illustration of how well-meaning international support to grassroots activists often crosses boundaries and becomes the opposite of empowering. Such support elevates activists into an off-kilter, precarious elite, while encroaching onto the most intimate aspects of their lives.

Western governments, aid agencies and philanthropists have made it their business to protect human rights defenders from the threats that come with being an activist. Including threats to activists’ health and well-being, beyond the immediate impact of their work. How does this play out, if the currency of their relationship is, well, currency - and therefore power?

If you subscribed here because I’ve written previously about Russia, Ukraine, revolution and war, this story might seem like an unexpected change of tack. To me, as an activist from the West who works with activists in Russia, Ukraine and other Eurasian countries, those monumental issues on the one hand, and this much more intimate story on the other hand, are all on the same spectrum.

The “discomfort” in the name of this newsletter comes from watching powerful international institutions behave like invasive species in the ecosystems of local civil societies: they bring benefits, but they also crowd out, choke off, displace and distort, and they create dependencies.

This text turned out longer than I expected, with its succession of stories, covering some 15 years. Intriguing stories, the kind you won’t read elsewhere, and necessary, I think, to understand the point I’m working towards. But for those of you who don’t have a lot of time, or interest in the intricacies of the “defender security” field, I wrote a shorter version. It cuts to the chase, namely that ultimate story of displaced Ukrainian women activists, the question of vibrators, and what it implies.

You can read that executive summary version here. Or stay on this page for the full story.

A thing called Defender Security

When I started working with activists in Chechnya almost 20 years ago, it was an intensely dangerous, violent place and time. The separatist-Islamist militants were still a force to be reckoned with. There were constant skirmishes in the forests and frequently in Grozny and villages, too. Occasionally, the underground militants managed to launch their trademark “spectacular” (as in spectacle) terrorist attacks beyond Chechnya, as far away as Moscow. Grozny lay in ruins, the normal workings of society only just resuming. Ramzan Kadyrov was chomping at the bits after his father’s assassination in 2004, while enveloping the republic in egregious human rights crimes against anyone suspected of supporting the militants and, increasingly, people criticizing him or standing in his way. He was appointed president of the republic in 2007, months after turning 30 and becoming formally eligible.

During this period, local civil society organizations were coming into their own, albeit with fits and starts and in ridiculously adverse conditions. Some had been set up a few years earlier, during the height of the war, to serve as local implementing partners for international humanitarian aid groups. This wasn’t necessarily opportunistic on their part. Most of their leaders and staff were thrilled that humanitarian aid funding enabled them to do good things in their community, like psycho-social work with children or prostheses and rehabilitation for amputees.

Much of the human rights work on Chechnya - documentation, advocacy, litigation, media outreach - had been done by Russia’s long-established and large human rights organizations like Memorial, which had opened offices in Chechnya and hired local staff. There were also a number of locals who had started campaigning, triggered by injustice and loss they had suffered in their lives or propelled by their aspirations for leadership and prominence (with other routes, such as politics or business, being closed to them, especially if they were women). The more enterprising ones among them had registered NGOs, a few had even won their own foreign grants.

I wanted to support local activists and their fledgling organizations, by prying open access to the opportunities, resources and platforms that had until then been available only to Moscow-based or international organizations. This sounds more grandiose and straightforward than it was. It meant writing their grant proposals and budgets for local activists, reminding them of deadlines, pleading to get seats at international conferences or for meetings with critical interlocutors, coaching them for those conversations and handling basic logistics like visa applications. Scrounging at the margins, really. But it helped me understand these activists: their lives torn by grief and trauma, their dreams for their community and ambitions for themselves, the complicated nets of social and political constraints that entangled them, the enormous stress and fear they lived under every day.

Remarkably, they believed that far-away institutions, of which they understood little (and preferred to keep it that way), would inexplicably provide substantial resources to fund their work, enable their leadership and lift them to a different, simultaneously more exciting and more secure, life. Maybe, I thought, this was because such unfathomable disaster had befallen their community, undeserved and out of the blue, and therefore equally inexplicable support from far-away places must have felt like restoring the universe’s moral balance.

It had always been dangerous to be an activist in Chechnya, but when the militants grew weaker and the Kadyrovtsy were no longer tied up with fighting them, the threats against activists were thrown into starker relief. As Ramzan Kadyrov started building a quasi-totalitarian system, any activist, even those doing innocuous, non-political, quiet things, like art therapy for traumatized children, would face suspicion and intimidation, if only for being busy-bodies and not keeping their head down.

Thinking of human rights defense as a purist pursuit set apart from ostensibly pedestrian, social activism, as inherently more impactful or irritating to those in powert, is a fallacy. In Chechnya, it was “saying bad things about Chechnya” (meaning, making a problem visible by trying to address it, the basic job description of any activist) that especially riled Kadyrov and a class of men serving in his proliferating security apparatus and enjoying limitless impunity.

Around this time, as my local colleagues were forever dealing with threats, I learned that something called “defender security” was - a thing: an emerging, separate discipline of civil society work, with its own norms, practices and institutions, if, at the time, still quite obscure. That defenders need to think about their security seems self-evident. People who challenge powerful institutions always face a backlash, and it makes sense for them to be prepared. But it is also counterintuitive, because the mythos of the human rights defender to this day demands sacrifice, superhuman courage, tireless exertion, self-negation, a lone wolf existence.

I started evacuating defenders facing threats and got to know one of the leading thinkers on defender security, or rather its 2.0 version - “integrated security”, a feminist, intersectional concept that centers human rights defenders as ordinary, complex human beings with full lives and elevates (mental) health care to the same level as “classic” threats, like harassment by the security services.

Not long after, one awful day in July 2009, Natalya Estemirova, the brilliant human rights investigator at Memorial’s Grozny office, was kidnapped and murdered. Her death made global news and caused shock, horror and heartbreak among local activists. A month later, another pioneering woman activist, Zarema Sadulayeva, who’d been helping child amputees, was killed in much the same way. Both women had been larger-than-life leaders, respected, admired and loved by many of their peers in Chechen civil society. Local activists were in a state of catatonic panic, fearing that any one of them might be next.

From that time and what feels like for years, everything my colleagues and I did became about defender security. Mostly that meant evacuations. For the next decade, practically until the pandemic started, we were constantly evacuating activists from the North Caucasus, either to somewhere safe in Russia or abroad. It was a decade of grant-writing, travel logistics, finding housing, schools for their kids, places in therapy. Virtually all of them were able to go home after a time-out and continue their work.

The default assumption by Western experts about activists in troubled places like Chechnya is that they fail to reach their stated goals and constantly run into obstacles because they lack capacities and therefore do things wrong. So the initial response to the acute defender security crisis after Natalya Estemirova’s murder was “they need training”.

The technocratically-minded professionals in the international democracy promotion industry assumed that such training had to be about encrypting emails, uncovering spyware on phones, magic legal phrases to pronounce at an arresting officer so he supposedly can’t touch or harm you. I remember sitting through a lot of mansplaining about how surely, this problem was all about technology and therefore could be resolved with technology, too. I remember some truly awful apps and gadgets. I even heard senior Western civil society experts recommend we hire retired military personnel as trainers, because “these guys really know security”. They think of the lives of human rights defenders as a James Bond movie.

The notion that activists could train their way to safety was absurd, but my colleagues and I went along with it. Soon, they let us determine the content of “training” ourselves (no more James Bond stuff). Most importantly, “training” meant going away together and spending time with each other. Integrated security practice starts with creating safe spaces, where activists build solidarity and trust, by getting to know each other better. Taking our colleagues outside the North Caucasus and even Russia for retreats made perfect sense.

So far, so good.

Integrated security also insists on mainstreaming defender security practice into everyday work and planning. Break it down to the standardized unit of civil society work, the project, and it means budgeting, in each project, resources for team mental health, staff security reviews, emergency slush funds to put someone on a plane at a moment’s notice. And regular time-outs, especially if the place in which activists live and work is toxic, drenched in violence and induces a permanent state of fear. This meant retreats scheduled at regular intervals, serving a mixed function: a safe space in which acute, sensitive security issues could be discussed, but also respite and recuperation from high-stress conditions at home.

It took years of networking, coalition-building, begging, pleading, lobbying, grant-writing and more grant-writing to scrape together the resources we needed to run the women’s rights programming we’d wanted, in the way we wanted, with feminist, integrated defender security built right in. When it finally launched, it was transformative. It became a source of strength, courage, safety and well-being among the dozens of women activists that joined together for this initiative, because they felt taken care of, by each other.

We had a financial cushion we could spend at a moment’s notice when any of our colleagues faced a threat, emergency or crisis. It didn’t have to be the stereotypical “armed masked men knocked at my door at night”. It could be a breast cancer diagnosis, a traumatic divorce from a violent husband, or burn-out. We’d evacuate her abroad, whether she needed to get away from security services breathing down her neck or relatives forcing her into an arranged marriage. Once a year, we could all meet somewhere beyond Russia’s borders, in a (modestly priced) beauty spot, for a retreat with rehabilitation and well-being built in.

Still so far, so good.

Integrated defender security, from a feminist and intersectional perspective, made sense to me and continues to do so. Human rights work is personal. It will envelop the whole person. Boundaries start to blur, activists absorb too much of strangers’ pain, deal with vulnerable and difficult people day in day out, despair of all the horror in the world and the slow pace of change. They stop reading good books because there are always stacks of dreary reports to plow through, and they stop writing clever, elegant prose because there are always soul-killing grant proposals to crank out by neverending deadlines. Their family and friends don’t understand or support them, and their children keep texting that it’s late, there is no food in the house, and mum, when are you coming home?

To remain whole and human and able to sustain their activism, activists need to be intentional about the other areas of their lives: their health and mental health, relationships, families, personal and intellectual growth, relaxation, but also pedestrian things like preparing their taxes. They should eat well, exercise, get their pap smear and breast exams, wear seatbelts, but they should also treat themselves to cake or cocktails, sleep in, play with their kids, chat the night away with friends. We - their colleagues, allies, donors and the adoring public, any of us who are farther away from the worst threats and stresses - do well to treat them as ordinary people with jobs, lives and needs, not self-sacrificing superhumans.

Since the world is a patriarchal, misogynist place, women activists in particular need to know their bodies, love themselves and claim their sexual pleasure, not silence that side of themselves because everyone expects them to be dour, ascetic saints. That’s what a forthright young activist from the Balkans told a circle of North Caucasus women at their first meeting. In the latter community, talk of sex is utterly taboo, so much so that people don’t pronounce the names of body parts. Most of them maintained a convincingly blank expression, until one of them blurted out “what do you mean, love ourselves?” They started giggling. One older psychologist said mildly “now, now, ladies, this is important, it’s good to talk about this”.

Activists should have work-life balance.

This sounds self-evident and mundane, but it goes against the grain of the archetype of human rights defenders, dissidents, activists that prevails in the communities where they serve, and in the West, where we get our vicarious thrills from picking heroes in benighted hellholes. I was, and still am, all for work-life balance.

So far, so good.

She is a woman just like us: knotty issues emerge

Back when we started centering defender security practices in our work, women activists from the North Caucasus had long been underdogs, clawing their way to the resources, platforms and recognition that usually accrued to international organizations, or elite, Moscow-based Russian NGOs, or their peers from donor-darling countries like Georgia. In many ways, they still are underdogs, forever constrained and sidelined by their harsh surroundings. But on integrated, feminist defender security, their knowledge and practice became more advanced and confident than anywhere else I worked. It took years for the rest of the world to notice, but eventually it did.

Practicing integrated defender security brought knotty issues to the fore, starting with those annual retreats. The activists wanted them to be longer, with more time just for hanging out, because “this is the only vacation we get”. The retreats were not meant as vacation, though. What’s more, we had always made it a point to pay all team members large enough salaries to cover all their expenses comfortably, including vacations.

Surely, spending your own money on yourself, on your own vacation and enjoyment, was more feminist and empowering, more in line with integrated defender security principles, than trying to squeeze a half-day of extra downtime from a tight project budget? More feminist and empowering than depending on the kindness of strangers?

Our colleagues could spend their salaries any way they wished and need not report to anyone about it, let alone their donors. Not so with the retreats, which were part of the project and thus had to be reported on, in great, revealing detail. The activists’ retreat-vacation, by their own admission the high point of their year, their spiritual and physical booster, was directly in the hands of far-away, unaccountable institutions.

This felt uncomfortable. It wasn’t work-life balance.

It gets knottier still. Most women in the North Caucasus, married or single, old or young, can’t go on vacation by themselves, whether they can pay for it or not. They’re not supposed to ever slip away from their relatives’ prying eyes, so as not to risk the family honor. At best, an activist could pay for a vacation, on which she’d then have to go with her mother or brothers or her husbands and in-laws. Meaning, during that vacation she couldn’t wear jeans, let her hair down, hang out in cafes, play pool, dance the night away, go swimming and really, truly relax. In some conservative families, she couldn’t even sit down at the table while her in-laws eat.

I write “at best”, because in general, women in this region aren’t supposed to have a good time, relax or take care of themselves at all, even if their family is with them. They are supposed to sacrifice themselves for their families’ convenience, comfort and reputation. A woman who enjoys herself is suspect. In the North Caucasus, men habitually go on on holiday alone, without their wives and children, who would only cramp their style.

Incidentally, that’s why we’d made attending our annual retreat a work obligation. Many of our colleagues needed that argument to get their families’ permission to go: if I don’t attend this, I don’t get paid and might lose my job (no, my brother can’t come along to keep an eye on me, either). It was still touch and go for some of our younger team members every time.

Right away, our team members wanted to bring other women along: their sisters, their friends, their colleagues or women they had helped in the course of their work. I was forced to remind them that our budget was tight, and how could they expect to spend hundreds of dollars on some random woman, and what if all of them wanted to bring along a friend?

But my colleagues were seeing right through the artificial constructs and categories the Western civil society industry likes to erect. She is a teacher, they’d say, she is a woman just like us - a feminist, she supports women and girls around her. She’s been through a lot. She needs this. They refused to accept that our feminist retreats, this unique chance to get away without chaperones and focus on their well-being, should only go to themselves, because they had been deigned special and more deserving of care by virtue of being an “activist”. Especially if what made them “activists”, singled them out from women just like them in all other respects, was the fact that their salary came from a foreign grant.

Our colleagues also wanted individual psychological rehabilitation, year-round, as a function of our joint work and thus paid for from project budgets. After all, they argued, they’d been through a lifetime of devastating trauma, from armed conflict, loss of family members in tragic circumstances, violations of their rights, fear, gender-based violence. All true.

But, I wondered, would you really want your employer to pay directly for your therapy? Your employer whose funding depends entirely on mercurial, opaque foreign foundations and bilateral aid programs, who spend money on women’s rights in the North Caucasus for reasons no grassroots activist fully understands, because they are never fully explained?

Do you want those far-away, unknowable and unaccountable foreigners, who already have so much power over your livelihood, to hold the key to your mental health as well? Do you want them to play such an intrusive, existential role in your life? What about your privacy and autonomy? Your work-life balance? Is this empowering? Healthy? Is it feminist?

Elite formation instead of equal liberation

By the time we were having these discussions, around 2013/14, defender security had reached the mainstream of the global democracy promotion industry. When feminist foreign policies also started going mainstream not long after that, Women’s Human Rights Defenders and their security became an ubiquitous acronym - WHRD - and an especially fashionable cause.

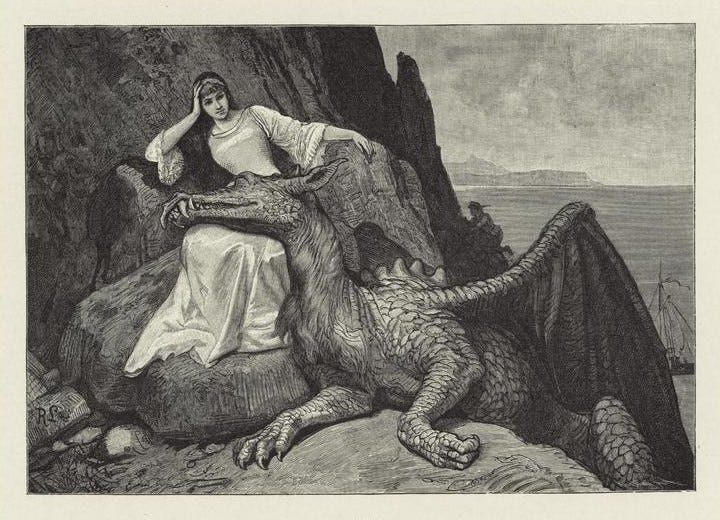

The WHRD is the perfect damsel in distress for 21st century Western diplomats, development aid officials and TED-talk organizers: as courageous as she is decorative at awards ceremonies, as emblematic of the diversity we aspire to as she is of democracy-promotion teleology, as inspiring as she is vulnerable and dependent on our, Western, protection. Because the WHRD is a woman, she is conveniently non-threatening, too.

Still, so far, so good.

This new interest in WHRD security meant resources, recognition, affirmation and it enabled us to keep each other safe and well. However, once WHRD security became fashionable among mainstream foreign aid policy-makers and donors, the competitiveness and elitism that plague organized civil society reared their heads in this area, too.

Organized civil society (think registered NGOs, with grants, projects, brands, international networks) is a viciously competitive and steeply hierarchical space. Human rights and social justice movements should question and dismantle all forms of oppression, exclusion and silencing, but instead these ills are often reproduced and exacerbated inside organizations and movements. One eminent North Caucasus women’s rights activist complained to me that another activist from her region had been invited to an international conference, even though she was a peasant from a village, who spoke Russian with an accent.

Or look at the biographies of some of Russia’s prominent human rights defenders, especially in Moscow. One of them has repeatedly questioned the “new ethic” (that’s how Russians irked by #MeToo refer to social norms against sexual harassment). There is nothing wrong with a man being chivalrous towards a woman, like helping her into her coat, she posted on social media. I learned this from my grandmother, who was a great lady, with servants, before the revolution.

In the years leading up to the the pandemic, with defender security trending and funding suddenly available, at least for countries that had been designated dangerous for activists, there was a brief boom in security and well-being retreats, offered by international NGOs. One such initiative was for defenders from the North Caucasus. These retreats were incredibly plush: extended stays in high-end tourist spots, a full package of mental health care, yoga and the works, several times a year. Those lucky enough to be invited were deeply impressed, moved, grateful.

But these retreats were held by an outside organization that didn’t know local civil society circles well. Since attendance was invitation-only, you had to be prominent to net an invitation. In a region where most human rights defenders can only stay safe by doing their work quietly, “prominent” meant affiliation with one of Russia’s big human rights organizations, or grant funding from one of the big foreign funders, or having won an international award. Or you had to be friends with one of the prominent ones.

Another Moscow-based European organization also started holding retreats, feminist ones at that, for women activists, with a focus on mental health and burn-out prevention. The Moscow-based organizer loudly and proudly announced it on Facebook, gushing about how important self-care was, how they’d checked every feminist box when creating the program, how much she was looking forward to it. I remember a middle-aged Chechen activist responding to this glowing post. How can we participate? You know how scary and stressful it is here in Chechnya for women activists. We need this so much. The answer from Moscow was sorry, but it’s invitation-only and we already filled all places. I hear there are retreats for activists from your region, go attend those. Except (see above) they were invitation-only, too.

One psychologist and activist, who has dug deeper into protecting and empowering women defenders than anyone else I worked with, coined the term “five-star syndrome”. It refers to the practice of whisking defenders out of their usual environments (in poor countries in the global South, in conflict zones and refugee camps etc.) to conferences, and increasingly also security and well-being retreats at, well, five-star hotels. It does something to their mind, she told me, they lose their sense of belonging to their community, they become displaced in the void between their modest, struggling lives and those luxurious spaces. They come to think of themselves as different, special.

Years later, I heard a Georgian labor activist describe how the only times she enters a five-star hotel in her own country is when she is invited by international organizations to meetings about labor rights. One of their international partners, a well-meaning, sympathetic woman, once even invited local activists on a helicopter ride, because they should have something nice, too.

A parallel universe in Ukraine: all is well in the “vibrant civil society”

Here, the story turns to Ukraine. The self-determined work on women activists’ solidarity, mutual support and security we’d been doing in the North Caucasus had been noticed by feminist peace organizations, who asked me in 2014 to help support women activists across Ukraine. Long (life-changing, heart-rending) story short, over the course of several years, I traveled the length and breadth of Ukraine, befriending, and learning from, women activists of all backgrounds. Some have been featured in this newsletter.

When I started working in Ukraine, it had been a little over a year since the Maidan and months into the armed conflict in the Donbas, and women activists were already running on empty. They had thrown themselves into humanitarian aid, evacuating civilians, assisting IDPs, equipping the military and were scrambling to provide psychological assistance to veterans returning damaged from the front. They were filling in for a failing state, plugging holes torn into the social fabric by devastating austerity policies, pushing to be heard in the post-Maidan “reform” frenzy. Some had fled conflict in eastern Ukraine and left everything behind, some kept returning to the frontline to help civilians. Quite a few of them had also faced violence, trauma and threats because of their activism, including from ultra-right extremists and security services. All that in addition to the everyday male violence in women’s lives. They were exhausted, and no relief was coming.

Some of them had become activists recently, but many had been in this line of work for much, much longer. However, none were aware that defender security was a thing: that they didn’t have to sacrifice their life, health or sanity to be true activists; that there were well-established, intersectional best practices for staying safe; that there were specialized organizations and emergency funders who were on their side and ready to provide support. After years of centering defender security in our work in Russia and watching it become a much-hyped, global cause célèbre, it felt like I had entered a parallel universe.

On closer inspection, it began to make sense. In the discourse embedding Western foreign policy and aid, Ukraine had been designated as a little rough around the edges, but ultimately “free” and on the right track. It was just in need of some technocratic polishing, not fundamental liberation and democratization, like, say, Russia. If an embarrassing number of journalists kept turning up dead, this was portrayed as an unfortunate side effect of a raucous young democracy and grubby oligarchic infights, not systemic repression. If neo-Nazis doxxed feminists and beat up queer people, there was some concerned knitting of brows, but not much else.

Since Ukraine had made its much-vaunted “civilizational choice” in favor of being with the West, since its “vibrant civil society” was its international calling card, it couldn’t possibly be a place where human rights defenders faced threats. Therefore, defender security was simply not on the agenda, at least not for the major foreign aid players who set the tone. It wasn’t brought up at conferences, it didn’t feature in grant calls, no one wrote reports about it. Ukrainian activists were left to believe that living in fear and sacrificing themselves was their lot, and they must not complain about it.

Over time, this changed, but it was a long-winded road. Initially, I asked a few gentle questions: What about the fact that years after the Maidan and the start of war in 2014, activists were still referred to as “volunteers”, implying they must labor day in, day out, without getting paid? Why was it that the vast majority of these “volunteers” were women? Would people expect that much volunteering from men? [Response by young movers and shakers in Odesa: bitter snort].

It took one week of nightly heart-to-hearts at a summer school for one activist to admit that she was afraid to live in her own home after being doxxed, yet could not afford rent for another place and was bouncing between friends’ couches. I sat with her to write a grant proposal to one of the specialized security funders. It took much longer than usual, because at every step I had to assure her that yes, those threats were sufficiently serious, yes, she was worthy of assistance, yes, it was ok to ask for help, but also because we had to correct the presumption that Ukraine was a safe place for its “vibrant civil society”.

In the year before the pandemic, at the annual session of the UN’s Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), the largest feminist bash in the world, my North Caucasus colleagues took one knowing look at their Ukrainian peers, saw their raw nerves, exhaustion and sour mood and diagnosed that they were in urgent need of comprehensive support. So we made sure they’d meet with defender security experts and funders, coached them to spell out their needs and tried to take care of them.

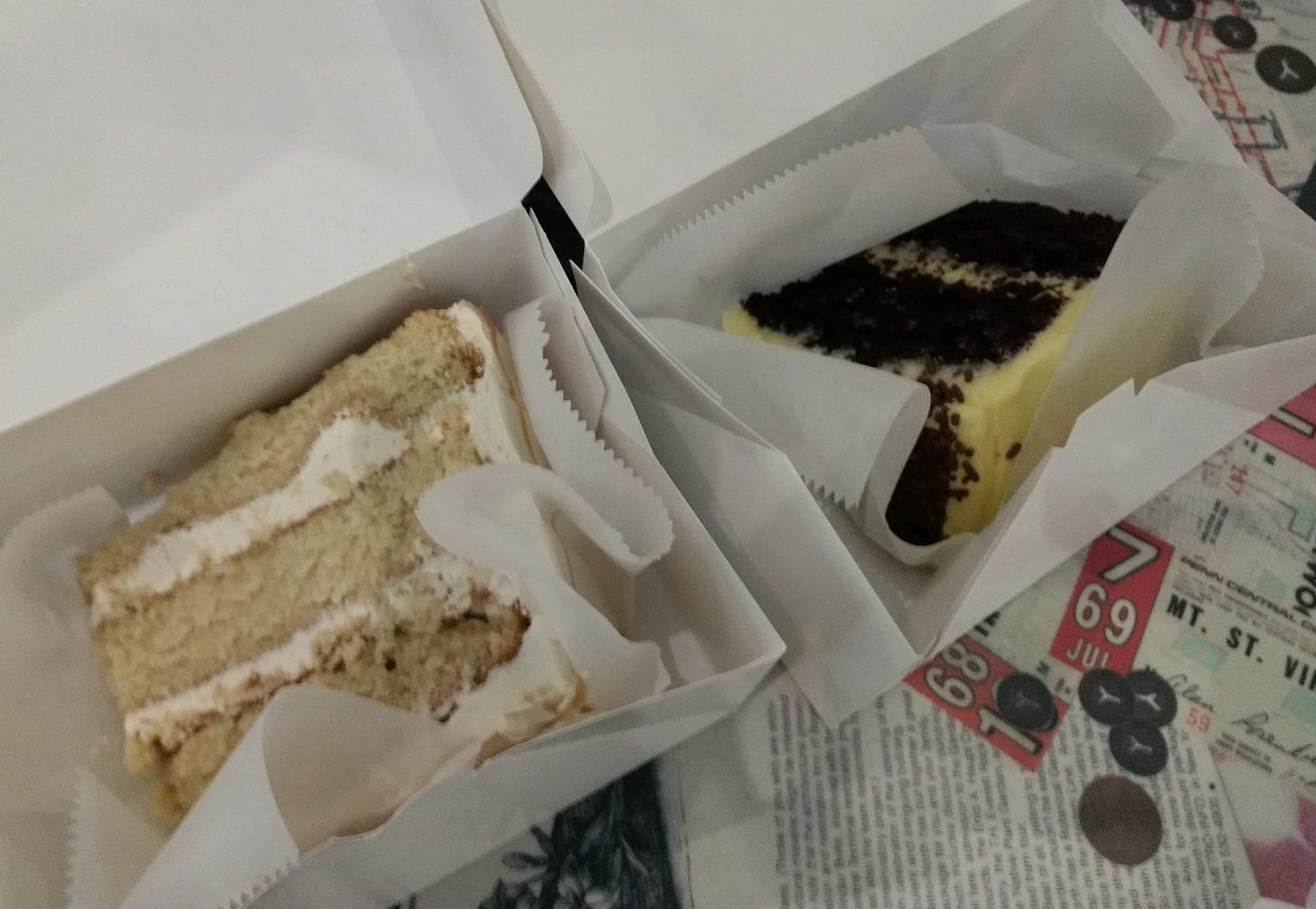

Rushing around Turtle Bay one blustery March day, one Ukrainian activist told me she lusted after a slice of proper American cake, stacked tall with layers and icing. Did I know where to get one around there? I did. When I posted later on Facebook that I’d been at a CSW event titled “Turning feminist peer care principles into practice", she thought she missed an expert panel. I explained that eating cake and chatting was the event; this was serious, essential practice.

Fast forward to the COVID pandemic. That it affected women and girls disproportionately and has set back progress on gender equality for decades has been widely reported (if largely shrugged off, despite the epic awfulness of this realization). The pandemic also stretched and strained women grassroots activists and their organizations to their limits and beyond, all over the world. Especially in communities where poverty, austerity, discrimination and political violence had long depleted healthcare and social services, women activists became the go-to, all-purpose first responders. They organized anything from food deliveries to volunteer ambulance services to online education and remote psychological support, keeping communities supplied and at peace during lockdowns, taking care of the sick and trying to fight against the explosion in domestic violence that accompanied the pandemic around the world.

In retrospect, the groundwork had been laid, just in time for the pandemic. Women activists from Ukraine, Moldova, Russia and beyond quickly found ways to talk to each other, vent, share advice and provide support. Activists in Chechnya set up “helping the helpers” group counseling, reaching their peers from eastern Europe to Central Asia online. I watched my colleagues being very clear and intentional about their indispensable role in their reeling communities and their own needs at the same time. They really came into their own.

Talk about indispensable: there is a handful of grant-making foundations that specialize in feminist, integrated defender security. I’ve mentioned them above, but I want to reiterate just how exceptional they are. They make fast, few-questions-asked emergency grants to women activists (and only to women activists), so the latter can protect themselves against threats, stay safe and sane, but also step up to save women and girls and entire communities around them in times of dire need or rare opportunity.

These women’s security foundations are unlike any other grant-makers I have worked with. These days, most donors swear up and down that they listen to their grantee partners and communities, lower barriers to access, introduce participatory processes, de-center themselves, cut bureaucracy and simplify procedures and communicate at eye level, and many of them mean it and try to do something about it, but from my perch, they largely fail.

Women’s security grant-makers, just a handful of them in all, are different in all the ways that matter. I won’t mention these foundations’ names here, because the women who work there deserve privacy, especially in the context of this story (the entire story, and the anecdote involving vibrators). They are true friends to the activists who turn to them for help.

Our power over their pleasure

The pandemic experience prepared many Ukrainian activists for the full-scale invasion that came in February 2022. Scratch that; nothing can ever prepare for war. What I mean is that Ukrainian activists, at home and together with their peers from Moldova to the North Caucasus, Belarus to Kyrgyzstan, had built region-wide virtual support networks, were able to set up Zoom calls, had come to appreciate each other’s wisdom and support, knew whom to message when they needed help.

Most importantly, Ukrainian activists, who’d been stuck in that parallel universe of their “vibrant civil society” that supposedly faced no threats, had by then absorbed the message that it’s okay to ask for help. That they could ask for emergency grants not just to save others’ lives, but also their own. That they deserved psychological counseling, breaks, help with living expenses. That they could get money to flee the war for good, but also to take breaks from war if they chose to stay in their communities and continue to serve them.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, the women’s security funds stepped up to the plate like I’d never seen before. They put millions in the hands of hundreds of Ukrainian women activists, faster and with more freedom for their use than ever.

A few months into the war, Ukrainian activists started planning retreats for themselves. They’d been in overdrive for months, their nerves and health were shattered. Many of them had not seen their colleagues since the start of the war, their lives having taken a peripatetic turn: fleeing missiles or occupation, finding refuge abroad, but getting restless and returning frequently to their home regions or setting up shop in another city in Ukraine, then leaving again for advocacy across Europe. One of them told me last month, more than a year into the war, that she had not stayed in any one place for more than a week since the war started. Another, from a now occupied southern city, opened a new office in Odesa; a city she - a middle-class woman nearing 50, with her own car - had never been to before the war.

A gift of vibrators

In summer 2022, in a regular Zoom meeting with these women’s security funders, a Ukrainian activist told us how their first retreat had gone. She was excited, glowing with that post-retreat high. It had been real, raw and meaningful, exactly as she had hoped. The participating activists had arrived exhausted. They were living as refugees in Europe, in often cramped conditions. This had been their first me-time since the start of the war and probably much longer. They loved that someone took care of them, that there was time to sleep in, that they had privacy.

The funders and other activists on the call nodded, sighed, oooh-ed and aaah-ed. This sounded exactly like what we all believed in. It made us feel vindicated and moved, vicariously.

The activists, the retreat organizer continued, had complained about their non-existent sex life. This was a good sign, it meant they were opening up, comfortable around each other, going deep into the “integrated” part of integrated security, into the work-life balance stuff. Most of them had not seen their husbands or partners for months, since men were not allowed to leave Ukraine. Some of them had their marriages unravel under the unbearable stress of war. In their refugee accommodations, they had to share rooms with others, sometimes with strangers. They were too tired, shell-shocked, overworked to think of sex.

More oooh-ing and aaah-ing around our Zoom group, faces on the screen scrunching up with empathy. Good job. These are the conversations we want activists to have. This is how we learn from them about the manifold, unexpected, granular ways in which war impacts women. We want them to be explicit and intentional about all of their needs. If women insist on their pleasure, instead of sacrificing it as they have been taught they must, you’re doing something right at your retreat.

“So”, the retreat organizer continued, beaming, “we thought that at our next retreat, we should gift them vibrators.” Giggling, whooping, applause all around our Zoom group.

One of the lovely, thoughtful, kind women from a women’s security foundation, smiling broadly and proudly, said “Go ahead, when you write the grant budget for the next retreat, put vibrators in it, we will pay for them, we want you to do this.”

It was a small moment in a long year of war, but it stuck with me. Something felt not right.

There was, once again, the haphazard elite formation. At a time when millions of Ukrainian women are refugees, lonely and sad, a dozen or so will get the gift of a vibrator from a feminist foundation. With all the feminist, sisterly love and giggles we try to send their way. Beyond those lucky few, several dozen or maybe hundreds more will be invited to any feminist retreat, where their hosts will do their very best to make them feel safe, comfortable, whole, taken care of and supported.

Millions of Ukrainian women will not go to a feminist retreat, or any retreat, let alone be gifted vibrators. But they are women just like us, my Chechen colleagues had said when they wanted to bring their friends to our retreats. They support other women and girls. They need this, too.

There was, once again, the issue of work-life balance. What a plodding, pedestrian term for something so fundamental and intimate. These activists would be given vibrators because of their work, from people they work with, paid for by institutions to whom they are visible only because of the work they do. They’d be presented with vibrators while sitting in a circle with their work colleagues.

There was the dependence on far-away, unknowable institutions for things that are not just existential (security, evacuating from a war zone, money for rent and food), but for the most private and indeed intimate needs. These institutions had already paid for these activists’ psychological counseling, cake and yoga. Now they would pay for their orgasms, too.

We like to think we seed empowerment, but this is its opposite, it is creeping intrusion and co-dependency.

An empowered woman would have her own disposable income, to spend on everything required for a safe, healthy, dignified, joyful life as she sees fit, with autonomy and privacy. Should we, then, aim to pay every Ukrainian grassroots activist a sufficient salary, so she could buy herself vacations, cake or vibrators? Of course not. Singling out activists for preferred treatment, livelihoods and lifestyles far above those of the communities they ostensibly serve, isn’t just unfair. It creates elites where there should be equality, solidarity and liberation for all, and estranges them from their communities.

The feminist activists who practice integrated defender security have been trying hard to get it right. We’ve come very close. Up to and including the wrong kind of close: too close for comfort.

The cost of our success is our failure.