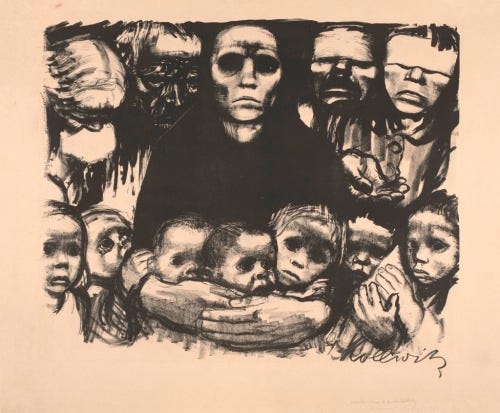

The time of women's tears

"First you cry because one man was killed, then the next man makes sure you have reasons to cry." Conversation with a displaced Ukrainian activist.

The following are excerpts from a recent three-hour conversation with an activist from eastern Ukraine, who has been working on women’s rights and armed conflict for a decade. She is displaced from her hometown, which was occupied in 2022.

“My grandmother used to tell me about the years after the war [World War II]. She used to call it ‘the time of women’s tears’: first women cried because their men had been killed in the war, then they had to keep crying because those few men who had survived were mostly no good, and not good to them. You cried because one man had died, then the next one made sure you had reasons to cry. Any weak, good-for-nothing, lame man could easily find a woman back then. In fact, he could find several.

I worry about my oldest daughter. Her generation may be facing another such “time of women’s tears”. A generation with not enough men left, when women have to make do with any men they can get their hands on.

Our government, and really the world, cannot give our men who have fought the attention they need, compensation for what they suffered, the care and healing. So what they do instead is they give them power. In the next elections, you’ll see, all the parties will fill their candidate lists with veterans.

You would think that women would be able to fill the roles left empty by men who were mobilized or killed. But there is no concerted effort, no program to allow women to do this. All the empty seats are given to veterans. Everyone can then pat themselves on the back.

This started happening already when the old war started, in 2014. In all the elections, you had veterans as candidates. The parties could show them off on TV, it made them look good. A lot of these veterans had to be cajoled into politics, and so most of them would get nothing done once they were elected, they were just sitting there doing nothing. They were not exactly useless, but just unremarkable people.

Back then, the country had also just introduced gender quotas, so when parties would draw up election lists, they would go “one skirt, one veteran, one skirt, one veteran”. It’s going to be the same now. We think elections are coming quite soon, maybe in spring already. It’s in the air.

But really, I’m most concerned about how to record our regional stories. Because no matter what people say and what we’re supposed to say and not to say, Ukraine’s regions are very different from each other. We have different traditions, ways of life, culture, foods. Remember, years ago, long before the big war, I said we should write a book, because if we don’t tell our story of war, then they will tell their version, and ours will be erased? Of course I never got around to writing anything.

The most urgent now is to record the lives and culture of the regions that have come under occupation. There is a group of people whose experiences I want to document. They’re the “ferrymen”, they help people from the occupied territories leave and go, via Russia, to Europe, sometimes from there on to unoccupied Ukraine. And back, too. Yes, it happens. People go back to the occupied regions, sometimes temporarily. Some even go back and forth. The “ferrymen” know all the tricks and routes. They see what’s going on in the occupied regions, how local communities are affected.

So we’re all the same in Ukraine, all citizens, supposedly. But we displaced people, we need so much more than those who still have their homes, their old lives. The locals have had two or three generations to build what they have – their houses, their careers, their reputation and networks in the community. We, the displaced, are handed food and clothes when we arrive, and from that moment we’re the same as the locals, no extra support. But we have lost so much. We cannot function like the locals. We can’t rebuild our lives.

Everyone here is speaking about reparations. About those frozen Russian funds and how they should be given to Ukrainians.

We have lost so much that is immaterial. We lost the men we might have married. We lost family support. We lost our childhood photographs. When the war first started, in 2014, I was a woman in my 30s. I had prospects, plans, potential. I was going to do big things. I lost all that. How can I be compensated for the future I never had? At what rate? At 10 hryvnia per year?

Who will compensate me for crying every night for three years? Not just for my 40 square meter apartment I left behind.

We are all the same and we are all united. But we need more than others, as displaced people.

We talk about peace plans and Marshall plans, and yet we don’t know whether we will live for the next half year. We talk about Trump and ICBMs, and then I hear from this woman [in a violent relationship], and does she care whether Trump was elected?

Domestic violence has exploded, it’s like a greenhouse for violence against women here. I can’t even find words to describe how much worse it has gotten.

Hero-worship plays plays a big role in politics, and then there is the mobilization issue. But imagine what is happening in families. I have text messages saved from women and girls who are in hell. When they turn to the police or other public institutions for help, and he’s serving or a veteran, they won’t touch him, at least not under the domestic violence law.

Lots of men are addicted to online gaming and betting. They might even bet away the measly child support payments families get from the government. So then she has to go to humanitarian aid groups and ask for baby formula.

Women are now the main resource for escaping mobilization. How so? Because she can give birth to a third child [note: fathers of three or more minor children are exempt from mobilization]. We’re seeing women giving birth at age 38, at 47 or even in their 50s, if necessary via IVF. Or couples adopt or even just foster a child that brings their total number of children up to three. Then he won’t be mobilized, and if he is already serving, he will be de-mobilized. Imagine what happens to those newly adopted and fostered children.

We have had more than a hundred beneficiaries in our project, but to me, the best success story is that of our coordinator. She was in an abusive relationship for ten years. She didn’t even work. One of those “why would you need to go out and work, I earn enough to support us” situations. She only told us months after we had hired her. She was able to leave him. That’s my best motivation, this is what success means to me. It is such a big project, which has done so much. But it also changed the life of this one woman, and now she keeps encouraging women around her.

Speaking of projects and donors. I have never met anyone who is as arrogant towards us as local Ukrainians who have been put in charge of grantmaking. Much worse than the expats we encounter. These local grantmakers are so standoffish. If we say hi to them, they don’t even say hi back. And we’ve known them for years, been to meetings and conferences with them. I’m very much for paying other women respect. If I consider a woman an authority in her field, a leader, I will stand up to greet her. But these local grant-makers are no authorities on anything. All they do is control money.

I want the war to end, so we can return to uninterrupted life.”

Thank you for writing this up. It reminds me of my reaction to the books about the effect of the Great Patriotic War on women’s lives: Night of Stone by Catherine Merridale and The Unwomanly Face of War by Svetlana Allilueva (sp?). It seems that the writing always privileged the heroism of the war, and left no space for women to talk about the less than heroic effect on men’s behaviour at home. I’m glad this woman has felt able to speak about this, as it’s very difficult and has a personal cost.