(Un-)Russian Revolutions?

Russians haven't risen up and overthrown their government like some of their neighbors. No, not because something is wrong with them.

In the debates raging since Russia invaded Ukraine, there is a recurring motif - “why don’t Russians protest the war, rise up against their government, get rid of Putin?” For those who pose it, this is a purely rhetorical question, to which the answer is a foregone conclusion:

Because something is wrong with Russians. No wait, all sorts of things are wrong with Russians, and that explains why Russia invaded Ukraine, and why Russians aren’t out in the streets protesting the war and overthrowing their government. They are incurably imperialist, racist, militarist and aggressive. It’s in their blood/genes/bones/history/poetry/collective psyche etc. At the same time, Russians are lazy, apathetic, cowardly, disorganized and incompetent, and that’s why they have not succeeded at rising up and ridding their country of its authoritarian ruler. Really, living under an authoritarian regime suits them just fine.

One up-and-coming Ukrainian journalist tweeted in all seriousness that Russians, unlike Ukrainians, “just don’t have a history of revolutions” (I’m not linking to her tweet, because that would be unkind).

There is a large body of social science research on popular uprisings around the world, a significant chunk of which is dedicated to the former Soviet Union, unsurprisingly. I won’t attempt to give a complete overview (I can barely keep up myself), but I want to talk about how these research findings mirror my hands-on experience all over the former Soviet Union, from countries with multiple “color revolutions”, to countries with no uprisings to speak of, to finally Russia, Belarus and Moldova, where mass protests took place, but failed (in their stated aims).

From what I’ve seen up close, different outcomes are not due to different culture, competence, skills, resources or any learned or inherent qualities people might have. The activists, protesters and ordinary “civilians” I got to know are no more and no less apathetic, cowardly, docile or accepting of repression and dysfunction in one of those countries than they are in the next. Uprisings or revolutions have turned out differently in different countries due to structural causes, such as how fragmented their political elites are. The public had no hand in creating those structural causes, either. This is no revisionist revelation. It’s well-established and should go without saying.

The debate on Russians’ supposed lethargy has been dripping with an essentialism that would not have passed in polite (Western) society until February 24, 2022. Now, this essentialism is like the bass line in all of our discourse, always there in the background, laying down the beat, at times getting to so loud it drowns out the other voices.

As Russians are being accused of racism (“they send ethnic minorities to fight their war”), they are being subjected to racism (“they’re different from freedom-loving true Slavs like the Ukrainians, because they have been interbreeding with Asiatics since the Mongol yoke”). I feel queasy even writing these things, but they are hardly the worst expressions of othering and dehumanization floating around these days. I’ve been seeing memes involving skull and facial shapes, and they are not meant as satire.

Once an entire nation has been reduced to essentialist stereotypes, denying them their rights and humanity typically comes next. When Russia announced mobilization in late September and large numbers of Russian men started leaving the country, the previous debate about a visa ban issue morphed into “should Russians be allowed to leave their country at all?”. Never mind that fleeing forced conscription, disproportionate punishment for refusing to fight and the risk of being forced to commit war crimes all constitute grounds for asylum, under international and EU law.

The tale of Russians’ eternal lethargy and preference for authoritarian rule doesn’t just beg to be corrected on the facts. It needs to be resisted because it leads down a dark and dangerous path.

These ugly attitudes conceal themselves under a faux-sensible veneer: if we close all borders and lock up Russians inside their country, they will channel their energy, rise up and overthrow Putin. If Ukrainians have twice over gotten rid of an unpopular government through vigorous street protests, why don’t Russians? If Iranian women can protest against forced hijab and the Chinese against COVID lockdown, despite the extreme risks, then surely Russians can come out into the streets. Oh wait, they still won’t do it? Then that’s more proof of their slavish apathy and organizational incompetence. Or of their imperialism and militarism, after all, polls show that a solid majority have been expressing support of the war.

Before I get into the main argument, let’s get all the insincere clutter, the apples-and-oranges stuff, out of the way. People will take risks and collective action for a change of policy, government or even type of government when they have existential, life-or-death needs and concerns, when their very survival and their most indispensable rights and dignity are at stake, where there are visceral despair and fury.

Iranian women throw off their headscarves, because nothing is more personal, more intimate, than what we put on our hair and bodies, and therefore, nothing is more intolerable than being denied this essential freedom. People in China dared to protest months-long COVID lockdowns, because being locked up is one of the most tangible, distressing, unbearable violations of our rights. From Argentina to Mexico to Poland, some of the largest demonstrations in these countries’ histories are against abortion bans. Few things are scarier in an existential sense than not having basic control over your body.

Conversely, I can’t think of any successful public uprising over discontent with foreign policy, not even over wars of aggression. There were protests in the US and UK against the invasion of Iraq, but they died down after the deed was done. Not long after, both Bush and Blair were reelected.

Mass street protests may be high-minded, but they are not altruistic. Those who call on Russians to rise up against Putin demand they do so out of empathy with Ukrainians’ suffering or indignation at an illegal war being waged in their name. That moral bar is so high that I cannot think of any national uprising that ever cleared it. And as Sergey Radchenko has laid out, Russians currently aren’t experiencing existential anguish, oppression or other hardship.

One more qualification: social scientists - unlike politicians, activists, the media etc - are reluctant to call these events “revolutions”, because a standard definition for that term exists and none of what happened in the 2000s in the post-Soviet space amounts to the required fundamental change in the constitution or form of government. Like the French Revolution (or the Russian Revolution…).

So why have mass street protests in Ukraine, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia resulted in a change of government, while comparatively massive and determined protest movements in other post-Soviet states left ruling powers intact?

The following is necessarily a condensed version of protests, uprisings and “revolutions” in the post-Soviet space since 1991, but it goes something like that:

these revolutions have succeeded only where political power is fragmented or distributed, where there are well-established, competing political camps of significant power

security and law enforcement services aren’t defeated or scattered in these revolutions, they just choose to switch their allegiances, to one of those alternative well-established political camps of point 1.

The mass protests that succeeding in removing governments (three times in Kyrgyzstan, twice in Ukraine, once in Georgia and Armenia) were all either directly led by political insiders, who’d served as ministers, MPs, headed political parties and had large informal political power bases (Georgia 2003, Ukraine 2004, Kyrgyzstan 2005 and 2010, Armenia 2018) or they were quickly exploited and captured by political establishment figures and camps (Ukraine 2013, Kyrgyzstan 2020). We don’t know the full story of what happened in Kazakhstan in January 2022, but from the available bits and pieces it looks like one of those alternative political camps tried to use the volatility of genuine public protests for something like a palace coup.

Where do law enforcement and security services come in? They’re a sine qua non for deposing a ruling elite. Their mandate, among others, is to prevent unconstitutional disruptions of power and defend the stability of state institutions. When they decide not to do so anymore, it spells the end of an embattled incumbent government. Why they do so at a certain point, what’s in it for them etc, we don’t usually get to find out. But we do know that they made this decision in every single change in government following public protests in the post-Soviet space in the 2000s.

The barricade-building, tire-torching, cop-chasing protesters from Kyiv to Bishkek cultivate the myth that it was precisely their “courage” and “blood” - armed, physical violence in street battles - that “defeated” the security services. When in summer 2020 anti-government protests, astonishing in their geographic and demographic scale and scrupulously non-violent, took place in Belarus, some Ukrainian commentators derided them for not building forts or burning things, for going home at night instead of camping out in the streets, telling them they wouldn’t achieve anything that way. I remember some of them calling Belarussians “sheeple”.

This is magical thinking. The security services in Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan were not defeated in any meaningful sense of the word. They didn’t crumble or run away scared. Nor did they come to their senses and sided with the protesters because of an ideological preference for the protesters’ demands or leaders. They “melted away”, as foreign correspondents like to describe it, only to resurface soon after, having switched their allegiance to competing political camps, whose insider powerbrokers made it worth their while. They facilitated the transfer of power. The SBU in Ukraine and the GKNB in Kyrgyzstan didn’t just survive repeated “revolutions” unscathed, but appear to have grown and thrived under successive new regimes.

In Russia, as in Belarus, such competing political camps do not exist. They have been dismantled or coopted by the powers that be or self-destructed by rendering themselves utterly unelectable as long ago as the 1990s. So even when protests turn massive and nation-wide and the regime starts looking shaky, as Lukashenko’s certainly did in summer 2020, there is no one who could flip the security services, no alternative political elites that could make them a serious offer. For Russian or Belarusian (or Tajik etc) security services, sticking with the regime is the only option on the table and probably the most appealing one anyway. So no matter how many Russians come to the street, how clever and well-organized they are, even how ready they are to build barricades and burn tires, that absence of viable alternative political elites means that toppling a government cannot happen like it did in Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan or Georgia.

The dogma that protesters have to be ready to camp out, burn stuff, seize buildings and ultimately beat and shoot at cops isn’t borne out by global comparative data. A Harvard study by Erica Chenoweth analyzing 323 incidents of mass action since 1990 shows that non-violent campaigns are far more likely to lead to change than violent ones.

Let’s look at this change a little closer. The ostensibly successful “revolutions”, those that ended with a president pushed out of power, didn’t “succeed” far beyond that. Those competing political elites I mentioned above slithered into power, where they reproduced more of the dysfunction and injustice that had brought protesters to the streets. As Volodymyr Ishchenko has characterized it, these are deficient revolutions: they change little in the basic political and material arrangements of the state, and nothing much improves in people’s lives, either.

The protesters in these events achieved a remarkable level of organization, but of the spontaneous, ad-hoc kind. They didn’t have comprehensive political programs beyond their ardently, if vaguely, expressed hopes and dreams, and even those were hardly unanimous. And they lacked the apparatus of well-established political parties or movements which could seize and populate the government apparatus. The resulting failure to fulfill protest movements’ hopes - primarily for greater social and economic justice - explains why in Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine, revolutions became repeat events. Or why, in recent years, Ukrainian activists told me that even though things were quite bad, they wouldn’t do another Maidan. It would be madness to try for a third time what hadn’t delivered already twice before.

For 20 years, I’ve been working with activists from every post-Soviet country (and talking to quite a few “civilian” non-activists, too). What I have learned aligns neatly with the social science and fills in the gaps with revealing stories. At the heart of everything my activist colleagues do are resistance, liberation and transformation, for greater justice, freedom, dignity, participation, equality and well-being. For some of them, this isn’t about the street, or only intermittently. They pursue long-term, patient strategies, anything from education, community empowerment, documentation, media and arts to litigation. But almost all of them have been out in the street themselves, have mobilized others to do so, and, most crucially, have worked tenaciously to protect everyone’s freedom of assembly.

The bravest activists I’ve known live and work in the most dangerous, repressive places, where public protests are out of the question. They are women’s rights activist in Russia’s North Caucasus, the belly of the beast. Women in Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetia face overwhelming oppression, violence and indignities every day, at the hands of their family members, community and local authorities. It’s crushing, infuriating, stressful, existential (think honor killings) and deeply personal (think grown women being told how long their skirt must be).

My activist friends would love nothing better than to flood the streets and scream about this at the top of their lungs. But it’s not safe. Holding a public protest, for women’s rights, would be the end of them. I’m not being melodramatic. Her brothers or uncles would see to it, long before any OMON officer could ever get hold of her (and if he did anyway, he’d just hand her back to her male relatives). It would also be the end of her cause and her colleagues, in ways that are much worse than even the grim, but calculated risks Russian protesters encounter elsewhere. It would be senseless.

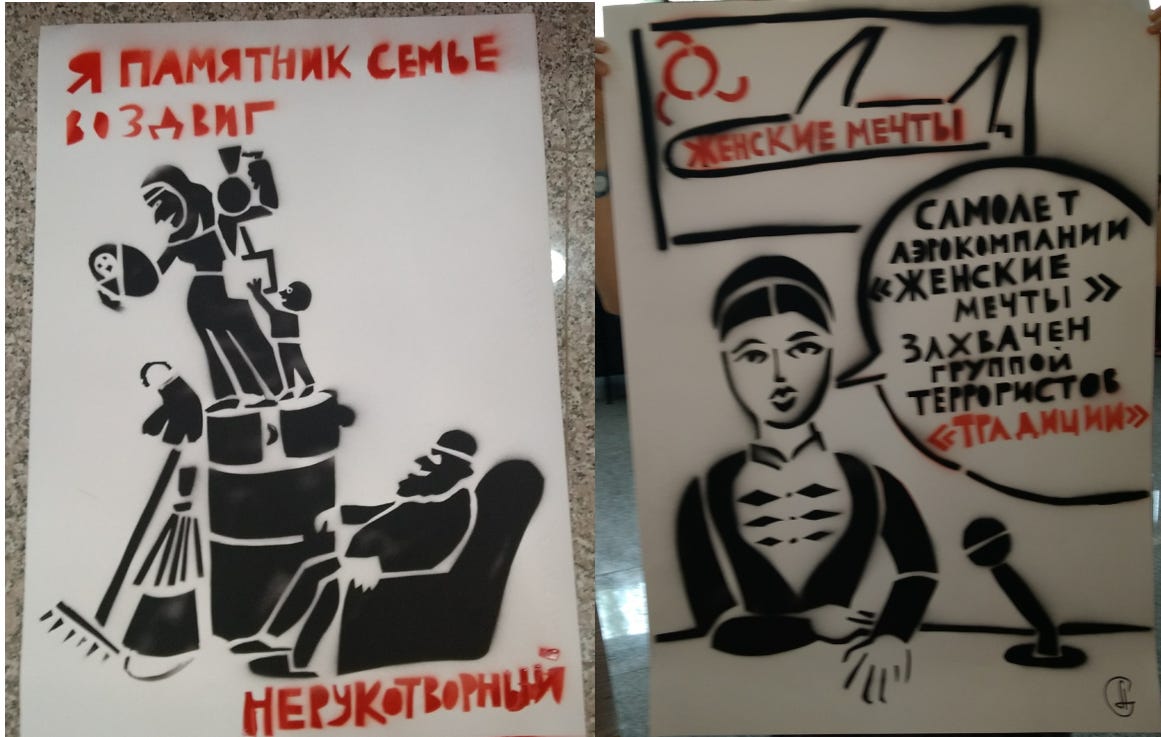

At one summer retreat a few years ago, at a safe distance, a feminist artist showed North Caucasus activists how to make protest banners with spray paint. They relished it. They mounted them on poles and paraded them around. We joked they better get it out of their system, because they could never do it at home.

And then, out of the blue, in fall 2018, it became safe for North Caucasus women to go out in the street and protest. In Ingushetia, anyway. “Safe” in the sense that their community reluctantly approved it, as long as they behaved, kept the genders segregated etc. What’s the big deal, some will wonder, it’s just Ingushetia, not Chechnya with Kadyrov’s scary quasi-totalitarian regime. But as Ingush feminists say, “our entire narod is our Kadyrov” (all community members police and oppress women). Mind you, protesting has long been dangerous for anyone in the North Caucasus, not just women. Only something utterly existential, desperate, something that cuts close to their very sense of being, could bring tens of thousands to the street, in tiny, conservative Ingushetia.

It was a land dispute that sparked it. Ancestral (isn’t it always?) land, marked to be handed to Chechnya in the course of formal border demarcation. Ingushetia isn’t just the smallest subject of the Russian Federation, in population and territory. It also lost a large chunk of its land after Stalin deported the Ingush in 1944, and when, after his death, they returned to their villages, they were now located in North Ossetia. From where many Ingush were driven out by armed conflict in 1992. The republic is shaped like a croissant with a bite taken out of it, wedged between North Ossetia and Chechnya and in places precariously narrow. Now Chechnya was making claims on their land and also on their distinct identity and autonomy.

By the share of the population (Ingushetia’s is only 509,000) out in the streets, these were some of the largest protests in Russia’s modern history. By 2018, not only was Russia’s protest-suppression well-established, but Ingushetia had only recently come out of years of violent repressions, including enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, torture, much worse than in the rest of Russia.

Yet for women activists, this protest was “safe”, because for once their community gingerly accepted their taking to the street. When they did so, it was out of righteous indignation at this land grab and patriotic sentiment. But it was also to assert their freedom to be seen and heard, in public and in the thick of it, wave a banner, claim a space for women. It was exhilarating. Then, the protests ended badly.

If we zoom out to the rest of Russia, where things are very different from the North Caucasus, there is nevertheless plenty of courage. The prejudiced narrative outlined at the top holds that Russians just don’t know how to do protesting right. But in my work with activists all over Russia, it felt like street protests were becoming the central issue over the last decade. All existing human rights organizations started mainstreaming freedom of assembly into their work, in addition to their everyday workload of LGBT rights, domestic violence, torture or documentation of Stalin-era crimes. New organizations, networks and movements were founded to work exclusively on protests and protesters’ rights, like the amazing OVD-Info (which also revolutionized fundraising from ordinary Russian citizens).

The focus of these civil society efforts isn’t the organization of protests. They leave that to those with political causes. That’s the correct approach, because human rights organizations should maintain neutrality. Instead, they have the back of protesters and try to keep the space for freedom of assembly open. Any protesters, for any cause, can benefit from this support system.

The scale, effectiveness, competence and coordination of these efforts are mind-boggling. Whether intermittent nation-wide protests or the far more frequent demonstrations over local grievances, by the time a protest is planned, everyone is falling into step: potential protesters are coached on their rights and how to conduct themselves during arrest and detention; apps are developed (and even used!); specially trained lawyers stand ready to defend thousands of detainees pro bono, showing up at police stations even before the notorious paddy wagons roll in; independent media and social networks report in real time, giving over their front pages to protest coverage; some of the best lawyers in the country turn cases into epic, precedent-setting battles with domestic courts and (until Russia left the Council of Europe after the invasion of Ukraine) the European Court for Human Rights.

In the run-up to protests and in their inevitably dire aftermath, most my acquaintances in any civil society function across Russia, full-time professionals and volunteers, would drop everything and get ready for the fall-out - reporting, tweeting or telegramming, monitoring, showing up at police stations and courts, days and sleepless nights of filing motions for thousands of clients.

There is more brain power, competence, creativity and coordination behind the all-Russian freedom of assembly infrastructure than any other area of democracy and human rights work in Russia. I’d argue that this nation-wide mobilization and coordination effort is one of the most comprehensive, competent, courageous and resilient anywhere in the former Soviet Union.

All this despite knowing that on the national level, protests would make no difference and would, on the contrary, lead to the imprisonment of protest leaders, crackdown on their defenders and further tighten restrictions for all.

Full disclosure: I wasn’t exactly thrilled by that. I was supporting grassroots activists and organizations in marginalized communities and felt this focus on protests crowded out resources and attention from other human rights work that was at least as important. I wanted Russian women facing domestic violence to get the immediate, energetic support detained protesters got, or violence against women to receive the breathless round-the-clock coverage that independent media dedicate to protests. Especially since it all felt so, well, futile. But I have to recognize the organizational skill, tenacity, solidarity, coordination, stubborn principle and courage behind this effort. I stand in awe of it.

With all this steely determination behind the protest movement in Russia, why don’t we see more protests now? Because, I hear from contacts, it wouldn’t just be futile and dangerous (they’re long used to that), but with stepped-up punishments and repression, it would put the very movement at risk of annihilation. They’re in self-preservation mode.

Self-preservation is an act of political warfare, according to Audre Lorde. I’d take the word of a Black feminist on that.

Then there’s Belarus. When I first connected with Belarusian feminists and human rights activists years ago, I was struck by just how much they were on their own, outside the usual ecosystem of Western grants, fellowships, study tours, conferences and donor-driven fads. On their own, and facing a well-oiled and mean-spirited machine of repression, they had built movements that were much more intersectional and in sync with average Belarusians’ concerns and priorities than I’d seen elsewhere.

In retrospect, this explains why the uprising that rejected Lukashenko’s stolen re-election in 2020 was so promising and so appealing. Of all the Maidans and color revolutions, this one checked the most boxes for a stab at true, not deficient, success, based on comparative studies like Chenoweth’s: it was non-violent, it was inclusive, it had inspiring and empowered leaders, and it had a well-articulated, constructive political program besides just toppling a hated president. The one crucial box it didn’t and couldn’t check was a fragmented political system with competing elite clusters.

In that harsh first year of the pandemic, Belarusian protesters did a lot of their organizing online, on zoom and YouTube streams. I listened to dozens of them, for hours and hours. I’d never been in spontaneous gatherings of strangers from all walks of life, talking about momentous political matters, in which women claimed leadership and confidently explained their aims and strategies while men patiently listened, didn’t interrupt or talk over them and asked respectful questions. And I mean never, not just “never in the former Soviet Union”.

In these YouTube livestreams, thousands would come together for hours to discuss their political goals, which fleshed out the “country for life” Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya had made the slogan of her campaign: improved support for single mothers, better maternity leave, kindergartens, urban spaces, pensions, empathic pedagogy in schools. Social and economic justice. Not allowing their struggle for Belarusian democracy to be captured by geopolitical zero-sum games. They talked at length about how they could not defeat the security services through violence and would instead need to persuade them to withdraw their protection from the regime and join the pro-democracy movement. The sophistication and calm optimism of these discussions left a deep impression on me.

Especially when keeping in mind that this took place against the backdrop of a brutal, extremely bloody and cruel repression of protesters. Tens of thousands detained, stuffed by the dozens into tiny cells for days, beaten, tortured, blood pooling on the floor. More than 1,000 ending up as political prisoners. Several leaders of the movement were forced into exile, another is imprisoned to this day.

It wasn’t enough. All the courage, sacrifice, solidarity, inclusiveness, constructive political planning and movement-building, the large scale and geographic spread of protests, even the recognition that they’d need to flip the security services and strategies for doing so, couldn’t crack a strongly consolidated authoritarian regime.

There are many more such stories, from Russia, Belarus and other post-Soviet countries, where people are no less brave, principled, ready to sacrifice, creative, clever, inspired, competent and well-organized than in Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia or Kyrgyzstan. The former might even have an edge over the latter in terms of capacities, forged in the pressure cooker of greater repression.

Add to this, as the Russian saying goes, “the porridge in which they simmer”: until repression gets right into your face, becomes deeply personal, existential; until socio-economic stress becomes unbearable and poverty unlivable; until governance becomes so dysfunctional it impedes everyday life, no country generates street protests with the necessary critical mass. Even then, Russia’s political elite isn’t fragmented into competing camps, one of which could flip the security services and thus seize power.

Ordinary Russians aren’t rising up in large numbers, because none of the usual conditions that trigger such events are present. (No, waging a war of aggression isn’t one of those conditions.)

The hyper-mobilized underground of routine protesters and the anti-war movement have been lying low in recent months, because they know there is no theory of change that ends with Putin no longer in charge. They are choosing self-preservation, although from what I can see, it’s not so much a choice as being forced onto them.

So much about Russians.

Now, what about us? We know it’s cynical and hypocritical to set impossibly high bars of altruism, courage and general miracle-working for Russians and then, when they predictably don’t clear them, revert to preachy stereotypes to explain what’s wrong with them. Will we be honest with ourselves and apply our established knowledge of political and social processes - of how and under which conditions mass protests actually depose governments - honestly, fairly, objectively? Are we going to do something about the bad faith prejudice, the facile essentialism veering into racism and othering that have infiltrated our discourse?

So very thoughtful from so much experience. This resonates closely with what I've seen in 50 years of anti-war, anti-imperialist organizing in the US.

Perfect article. Logical, concise, and perfectly shaped.

Thank you very much! Now is the time when we badly need this kind of analysis.